'Such a beautiful machine, its quality rated by all astronomers is recognized'. A biography of a virtually unused telescope.

Huib J. Zuidervaart (Gewina 26, 2003, 148-165) and (Van 'konstgenoten' en hemelse fenomenen : Nederlandse sterrenkunde in de achttiende eeuw, 1999, 151-154), Alex Pietrow (Eureka, nummer 58 - oktober 2017)

translated/edited by Erik Deul

Introduction: a remarkable telescope from a remarkable man

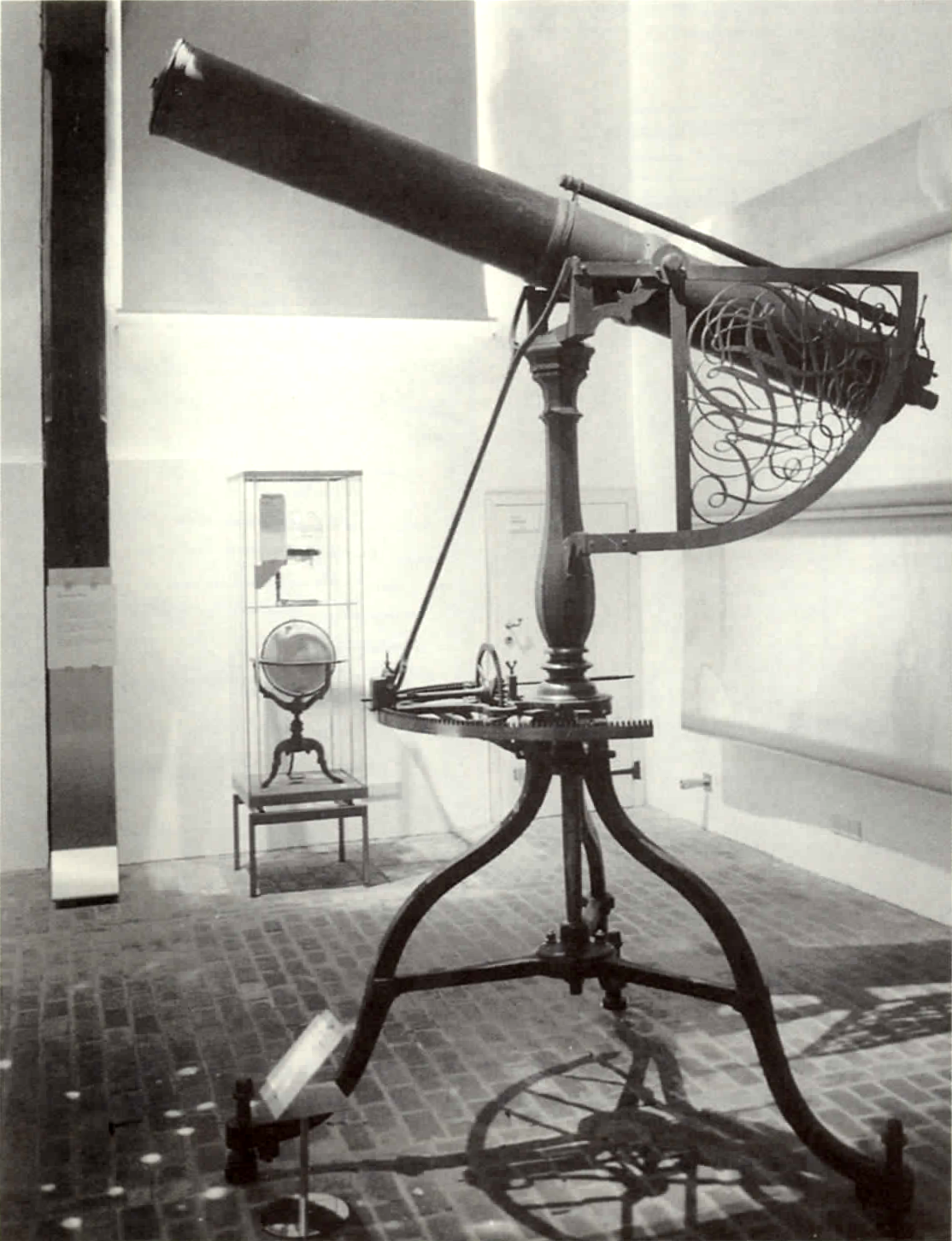

In the hall of the Leiden observatory, built in 1861, a remarkable reflecting telescope stood for decades, and according to tradition it was even used as a coat rack for a long time. This curious instrument, which was bequeathed to Leiden University in 1782, was entrusted to Museum Boerhaave in Leiden in 1989. However, as part of an external presentation of the museum collection, the telescope is located in the hall of the Gorlaeus building, the modern seat of the astronomy department of Leiden University.

This instrument was once one of the largest reflecting telescopes available in Europe. In the eighteenth century, various astronomers had a keen eye on this instrument. One of them was the French astronomer Joseph-Nicolas de l'Isle (1688-1768). In the year 1785 he was busy searching the heavens for a comet, the return of which was already reported in 1698 by the English astronomer Edmund Halley (1656-1742). This comet was all the more eagerly awaited because its return would provide a first confirmation of Newton's hypothesis regarding the elliptical orbit of these celestial bodies. Through an unnamed contact, De l'Isle had learned of some simple observations that the owner of the instrument — the Amsterdam merchant Jacobus van de Wall (1700-1782) — had carried out with his large telescope in the previous year. This was reason enough for De l'Isle to inquire about this Curieux d’ Amsterdam — which seemed— an extremely large telescope. Could this telescope perhaps be used for a search for the comet? — Arnout Vosmaer, the Hague administrator of the natural science collections of stadhouder William V, however, had to disappoint De l'Isle. In his response he stated that although van de Wall owned an exceptionally good telescope, this beautiful device was hardly used for astronomy. Vosmaer could, with De l'Isle, only regret that such a beautiful 'machine', the excellent quality of which every astronomer recognized, was not in more capable hands.

That Vosmaer was right is confirmed from other sources. Although over the years numerous astronomers have made their way to Van de Wall and his Amsterdam observatory, it is clear from all reports that this merchant was mainly driven by an optical — possibly even purely mechanical — interest. The travelogue of the Swedish astronomer Bengt Ferrner, who visited Van der Wall in 1759, provides a nice illustration of this. Although Ferrner characterizes the Amsterdamse koopman as someone with a good and clear mind 'had a great deal of knowledge of mathematics and physics', he missed two essential things in Van der Wall's observatory: the building lacked both an accurately plotted meridian and a reliable pendulum clock. Ferrner therefore concluded sharply: 'This shows that for Mr Van de Wall, it was more a matter of viewing the celestial bodies and share with his viewers his knowledge of optical theory, then to make a series of observations that can serve to show off the accuracy of astronomy.

This article aims to address this remarkable situation in which an Amsterdam private individual spared no expense or effort to produce a telescope that at that time represented the state of the art, but who on the other hand hardly used this instrument for scientific observations. If this telescope did not have to serve science, what purpose did it serve? In this story the main character will be the telescope itself, and not so much its maker Van der Wall. The scientific climate is reflected clearly in the fortunes of the instrument as in the reflections of learned contemporaries.

The maker: Jacobus van de Wall (1700-1782)

Van de Wall is not a well-known figure in the history of science. Some archival research shows that he was a wealthy trader who, at first glance, hardly distinguished himself from fellow merchants. He was born in Amsterdam in 1700 as the son of the merchant Johannes van de Wall and Elsebeth van Alste. In addition to their son Jacobus, this couple had two more sons and two daughters.

According to the register of the personal quotation of 74, father Joannes van de Wall lived that year as a 'rentier' with his eldest son Jacobus, who is listed as a 'merchant' and who at the time lived in a building on the Amsterdam Keizersgracht, between the Huidenstraat and the Molenpad. Afterwards, Jacobus van der Wall moved at least once more, because when he died in 1782 he appears to have lived in a house on the south-east corner of Keizersgracht and Nieuwe Spiegelstraat. At that time, Jacobus owned more real estate, including a warehouse called Delft on the Muidergracht, opposite the Hortus Medicus. He also owned a country estate called De Kievit, located just outside the Leidse Poort on the Overtoomseweg, in an area that was then called 'Nieuwer Amstel'. Although Ferrner described him as 'a childless widower' we have found no evidence of a marriage. While the estate of his unmarried brother Johannes contained at least two 'lady portraits', nothing of the sort is described in the estate of Jacobus. The only woman who is definitely in his life, was his 'resident' housekeeper Pieternella Brasser. When Van de Walls died, she was amply endowed with household goods, including his 'Papagaaikooi'.

Brother and business partner Johannes van der Wall, also childless and unmarried, inhabited in 1742 a canal house on the Singel, between the Oude Spiegelstraat and the Wijde Heijsteeg. Later would this brother move to a Herengracht house. Together with Jacobus van de Wall he was the head of a medium-sized trading house, the Company Jacobus Johannes van de Wall, which had an office in Amsterdam's Kalverstraat. The business activities of the two brothers were quite diverse. When we rely on the countless loading contracts preserved in the Amsterdam notarial archives, the main part of their efforts, in addition to some banking work, consisted of sailing ships to various destinations in the world at that time. For example, they shipped grains, seeds, peas, flax, rye, oats, hemp, camphor and wheat, as well as millstones and herring, to and from a wide range of places in Russia, Scandinavia, England, Scotland, the Netherlands, France, Spain and Portugal. There was also trade with places in East and West-Indie, but in this case it concerned only goods such as wood, minerals, metals and diamonds. However, the core business of their trade concerned Portugal. When the Portuguese capital Lisbon was destroyed in 1755 by a severe earthquake, then one of the eyewitness accounts published in the Netherlands comes from an employee of the Van de Wall company. This is also the first time that we have heard, in printed form, of a scientific interest of Jacobus van de Wall, who is referred to in this publication as 'merchant in Amsterdam and lover of the fine arts and sciences'.

The reflecting telescope: brief development history of an instrument

Ferrner was able to record the following about the history of Van de Wall's telescope. Years earlier, during a trip to England, he had wanted to buy a reflecting telescope with a four-foot focal length. However, the price asked for such a telescope had seemed excessively high to him, so that he had waived the actual purchase. Van de Wall, however, who - said Ferrner - 'was experienced in theory', had then decided to make a reflecting telescope himself.

Now, manufacturing such a reflecting telescope was less simple than it might seem at first glance. After the invention of the 'Dutch monoculars' around 1608, the lens-based telescope was gradually developed to perfection during the seventeenth century. And although it had already been devised in the first half of the seventeenth century that a telescope could also be made with concave mirrors, no one had actually tried to make such an instrument. The loss of light that occurred during reflection - compared to transmission through glass - was simply too great for this purpose. Moreover, there was no theoretical need for such an effort. Because why should one make an effort to achieve something what could have been improved in another way? That attitude changed with Isaac Newton. Around 1665 he realized that the refraction of light through glass is different for every color. This caused Newton to make the (which turned out to be incorrect) assumption that the color separation occurring with lenses was in principle insoluble. From that moment theoretical motivation arose for the construction of a reflecting telescope. In 1668 Newton indeed managed to make this instrument himself. Shortly before that, in 1663, the Scottish mathematician James Gregory had published his own plan for such a telescope. In that design, Gregory had combined a concave parabolic mirror with a smaller concave, but now elliptical, mirror. In theory, this mirror combination provided a sharp image just in front of the center of the main mirror. However, the practical construction of such a 'Gregorian' instrument initially met with difficulties to insurmountable problems. Newton therefore opted for a simpler design. His telescope became a hollow spherical secondary mirror, in combination with a flat metal mirror. By keeping the secondary mirror small, the deviation from the required parabolic shape was not noticeable in practice.

That Newton succeeded in his attempts can be called exceptional. His success is often attributed to his extensive practical experience, including alchemical experiments. In the decades that followed, only Robert Hooke succeeded in making a more or less working example of a reflecting telescope. Also a French design by Cassegrain, published in 1672, stayed at the drawing board level. Time would show that only thorough and prolonged practice in shaping and polishing concave mirrors would lead to acceptable results. In addition the fact that a suitable producible alloy for the mirror metal could not be easily found — mirrors once polished became dull very quickly - was the cause of the fact that hardly any reflecting telescopes were made in the first half century after Newton and Hooke.

It was not until around 1720 that the thread was picked up again by John Hadley, vice president of the English Royal Society. This gentleman scientist had ample funds and a sea of free time at his disposal. As a result, Hadley could afford to experiment extensively with a wide variety of alloys. For a good telescope mirror the metal had to be both dimensionally stable and highly reflective. These properties are often accompanied by polishing problems, unfortunately. The harder the metal, the more likely it was that microscopic pits would form on the surface. This promoted oxidation of the mirror, which was at the expense of both reflection performance and imaging quality. It also turned out to be difficult to make the metal into a homogeneous composition, which meant that polishing the metal surface had an uneven effect in different places. However, such problems often only came to light when the mirror was almost completed. It was therefore very important that Hadley had developed a test method with which he was able to detect deviations from the desired shape during grinding. The development of the reflecting telescope therefore owes a lot to wealthy 'enthusiasts'.

Only those who have an unlimited amount of time, money and patience, ultimately proved to be able to achieve results. The professional instrument makers, those who existed at the time, simply could not afford these time-consuming efforts. Precisely for this reason, Hadley consciously transferred the technical knowledge acquired by him and his employees to two professional instrument makers, namely Edward Scarlett (ca. 1688-1743) and George Hearne (1741). These two opticians would emerge as manufacturers of reflecting telescopes in the next decade. Initially they mainly produced Newtonian telescopes, but because of their ease of use, the Gregorian variant - now also technically feasible - was introduced as the reflecting telescope that soon became the most favourite, with the occasional cassegrain model included as a possible option.

Through Scarlett and Hearne the know-how on how to manufacture telescopes with mirrors spread rapidly among English instrument makers. The most successful of them was James Short (1710-1768), who focused exclusively on the manufacture of telescope mirrors. Thanks to this specialization, Short was recommended as the best constructor of reflecting telescopes in a standard work published in 1738. Because of this reputation, Short was the only telescope builder to be able to charge approximately double what was customary for other instrument makers. Given this well-documented fact it is obvious to assume that it was Short from whom Van de Wall wanted to buy his first reflector around 1740. Because compared to others, the price of Short's telescopes was certainly 'excessive' and that not only for a thrifty Dutchman.

The hobby of an Amsterdam merchant

It was indeed because of competition with Short that Van de Wall started to focus on the manufacture of telescope mirrors. Van de Wall appears to have spoken about his motivation to three of his visitors, namely the astronomers Bengt Ferrner (1759), Johann Friedrich Hennert (1769) and Thomas Bugge (1777). All three are fairly consistent about Van de Wall's account. Van de Wall stated that many years ago, when Short was not yet building telescopes longer than 4 feet, he had begun to manufacture such an instrument. He had polished the mirrors with his own hands, which he had cast into rough shape by a yellow caster. When he had managed to make several of these smaller telescopes, he decided to make a telescope larger than those being made in England at that time. At that point Van de Wall started working on his large 8-foot telescope, which by now is admired by everyone.

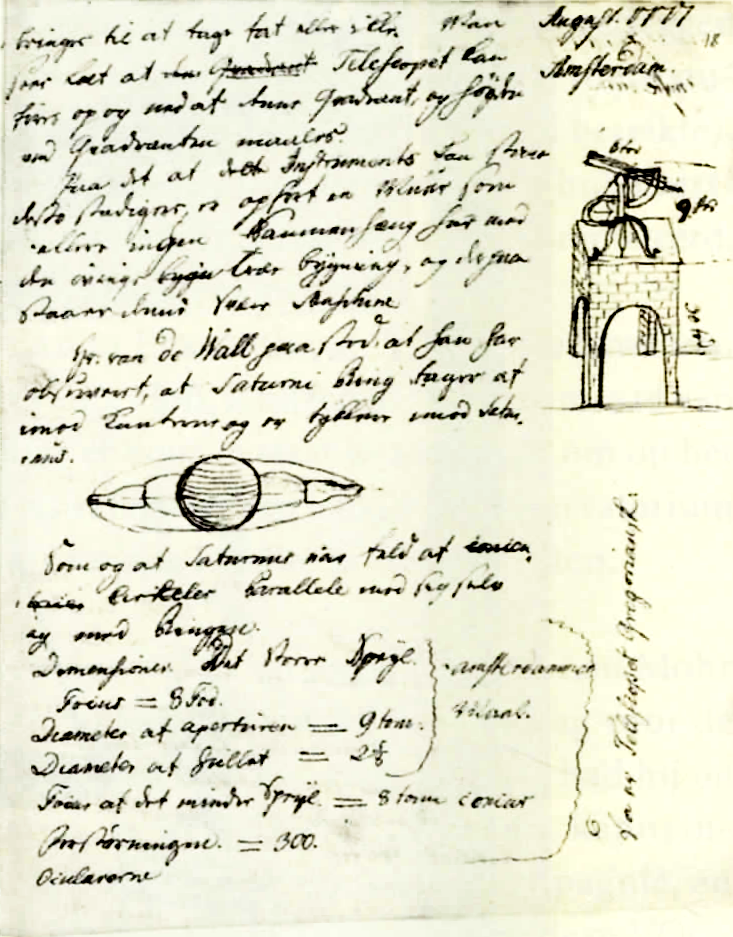

Once Short found out about this, Van de Wall said, he had made two telescopes with a length of 12 feet. In turn, Van de Wall did not want to be left behind in this competition. He then started working on mirrors for a 20-foot telescope. In 1759 when Ferrner came by, these mirrors were ready, but due to intensive business activities Van de Wall had not yet had time to try them out. That situation was unchanged when the Danish astronomer Bugge came to inspect in 1777. Bugge also got shown the completed mirrors, but because Van de Wall was now convinced that the housing of the telescope - and especially its base - would become too heavy and stiff, he had given up to build an even larger telescope.

It has long been thought that Van de Walls telescope must have been manufactured shortly after 1753. Making such an instrument was, as indicated above, no easy feat and Van de Wall must have had certain instructions or examples. Now the first Dutch-language book writing about the construction of reflecting telescopes was published in 1753. Jacobus van de Wall is included in the list and mentioned by name as one of the subscribers. It was therefore logical to identify that his activities happened after that year. However, the above account provides sufficient evidence for a considerably earlier dating of this instrument. After all, on the one hand, Van De Wall indicates that he is involved in the construction of telescopes which must have begun, after he - probably at Short's - had wanted to buy a four-foot telescope and on the other hand Van de Wall tells all his visitors that he already had his large telescope ready before Short started working on a 12-foot telescope. It is true that the date Short started the production of four-foot telescopes is not known for certain, but since Short make his first three-foot telescope in 1741 it is reasonable to assume that his four-foot telescope was also created around that time. Van de Wall can therefore only have started to manufacture telescope mirrors after 1741. However, because Short build his first 12- foot telescope (the largest he has ever made) before the end of the year 1742, this implies that Van of Walls large telescope must have originated in the course of that same year. This is assuming that Van de Wall has told a truthful story to his guests. In short, how credible should we assess Van de Wall? Could he indeed have had sufficient expertise in 1742 to produce such a large telescope? And assuming this is the case, why does this telescope only appear in historical sources sixteen years later?

A correct assessment of the situation requires a further introduction to Dutch national environment of natural science enthusiasts around 1740. It is well known that dilettantish interest in the natural sciences flourished around this time. Due to a combination of various factors such as prosperity, breakthrough Newtonianism, physico-theological justification, sociability, entertainment, curiosity about all kinds of scientific discoveries and the usefulness attributed to them for of society, the extent of enthusiast interest in the natural sciences had increased enormously in the thirties of the eighteenth century.

This raises the question of what can be said about Jacobus van de Wall's scientific contacts and the circles in which he moved. Particularly in 1741, the year in which he started the production of telescope mirrors, he appears to have been in close contact with a certain Dr. Johan Christoffel von Sprögel. This was one of the Scientific practioners who were working in Amsterdam around this time. Von Sprögel was born in Hamburg and trained as a doctor in Halle. By 1720 he had settled himself in Amsterdam, where he quickly manifested himself as an erudite man with great practical and theoretical skills. In 1722 he obtained a patent there for a 'newly invented fire extinguishing machine'. In the years 1738-1743 he translated most of the oeuvre of his old teacher, the German natural philosopher Christiaan Wolff, into Dutch. In the foreword to one of these books, Von Sprögel praises the scientific climate he found in Amsterdam. It is as if he has Jacobus van de Wall in mind when he writes: 'Where can one find people who are concerned about their extensive purchasing trade, and overloaded with temporary goods, can create joy for a part of their time spend exploring the secrets of nature, as to be found in Holland?"

According to a surviving prospectus, Von Sprögel had the intention in 1736 to provide lessons in physics and chemistry for the benefit of 'enthusiasts' in a 'special collegium'. He also refers to these plans in one of his translations. In 1741, however, von Sprögel singed a contract with Jacobus van der Wall in connection with a proposed mining project in Brazil. He was clearly approached because of his chemical expertise. As 'master melter and separator of minerals and metals', Von Sprögel had to supervise the manufacturing of ovens, stoves, and 'everything that pertains to the work in the mines'. If desired, he also served with 'apprentice and fellow masters' to travel to Lisbon and from there to Brazil. That this actually happened has not been proven, but since Von Sprögel can no longer be traced in the Amsterdam archives after 1743, his actual departure to Brazil is extremely likely.

Given Von Sprögel's versatile expertise- he possessed medical, technical, physical chemical and metallurgical knowledge - it is conceivable that he played a role in developing Van de Wall's optical interests. Von Sprögel too had Wolffs Optics, Catoptrica, Dioptrica, Perspective en Sphaerische Trigonometrie translated into Dutch and in the 'preface' of that work it is explicitly noted that this book was also intended for practical use. Or, to put it in Von Spröge's words: 'whoever has the desire to do some optical manual work, will at the same time find this informative to even be able to make the optical tools'. And it is precisely the latter what his employer, Jacobus van der Wall, eventually started to do! Although Wolff's book did not mention anything about reflecting telescopes (that was not possible, the German text dated from 1719), the book did contain all kinds of clues for making alloys for mirror metal. Pouring and patient polishing 'glass-like or spherical mirrors' was also amply discussed in Von Sprögel's translation

Van de Wall could also fall back on more expertise. In 1738 the first printed manuals became available describing the manufacturing of a reflecting telescope. From London came Robert Smith’s Compleat System of Opticks, which included a detailed account of Molyneux techniques. The same year a booklet was made in Paris Construction d’un Telescope de Reflexion, in which the instrument maker Claude Passement shares his personal experiences with the construction of such a reflecting telescope. This last book, according to the subtitle, was specifically written for those enthusiasts, qui souhaiteront se construire eux-meme un Telescope. And in 1741, of ll places, a pirate print of this booklet was published in Amsterdam. In short, when Van de Wall indicates to his visitors that he considered himself 'experienced in the theory' of the reflecting telescope quite early on, then that statement certainly is not inconsistent with the real possibilities.

A network of technicians

About the instrument itself, Utrecht professor Hennert provides most of the details. In In 1769 he was working on a new optics textbook and, according to him, he had already finished the text and sent to the printer when he was given 'the welcome opportunity' to get to know Van de Wall and his 'very remarkable work'. Hennert was immediately delighted with the instrument. With the permission of the owner, whom Hennert described as 'a very learned optician', he immediately decided to write a description of the telescope and included it in his textbook. He had questioned the owner about the way in which he had manufactured his mirrors. According to Van de Wall, it was best to use Japanese or Swedish copper in combination with English tin for the mirrors. He had discovered this 'after doing many experiments'. He arrived at an alloy of 32 parts copper to 13 parts tin. A larger amount of tin would give the mirrors a greater shine, but this operation would make them more brittle and also less suitable for polishing. Van de Wall praised this alloy so much that, according to Hennert, he did not doubt for a moment that mirrors could be manufactured with a double or even triple diameter, provided one did not cut back on 'costs or work'.

The question remains why Van de Wall's instrument remained hidden for so long. Because why would Van de Wall have gone to the trouble of constructing a reflecting telescope in 1742, only to finally arrive into the spotlight with this 'machine' in 1758? Utrecht professor Hennert provides a possible answer to this question. He spoke in 1769 about this 'pretty instrument', which 'remained almost unknown for a long time due to the modesty of the inventor'. Is that 'modesty' indeed the explanation for Van de Wall's years of silence? In any case, the characterization of the man seems to be correct. Ferrner also reports that Van de Wall was 'generally regarded as a very benevolent and well-behaved person'. Indeed, not someone who would shout his achievements from the rooftops.

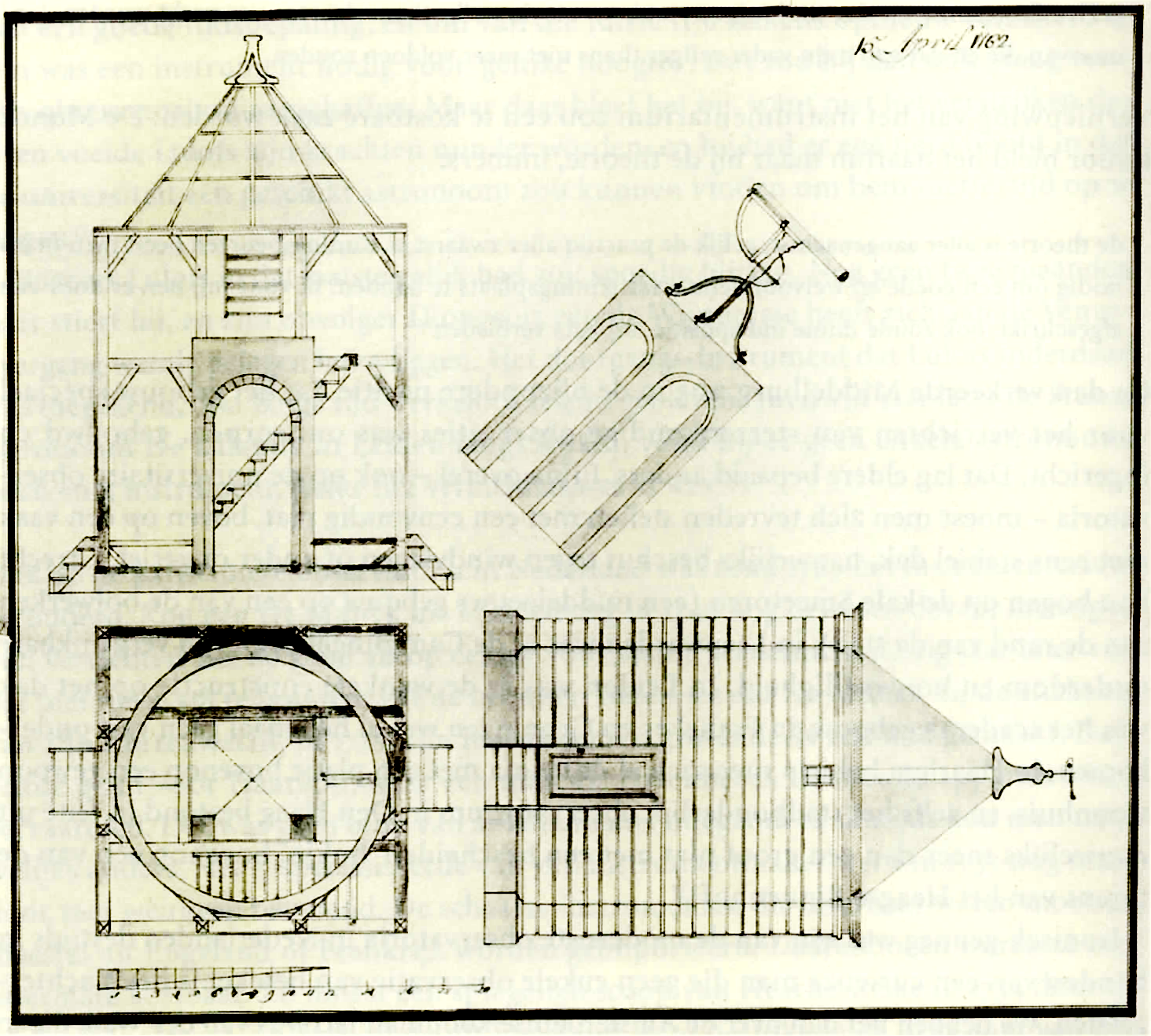

A more practical reason was perhaps that Van de Wall only had a suitable observatory from 1758. This observatory, which was specially designed for the large telescope, was located in the garden of Van de Wall's country estate De Kievit, just outside the Amsterdam city limits. Van de Wall bought this country estate in 1766, after renting it from 1758. Ferrner is reported to be the first visitor to this building in 1759: 'four pillars of brick, driven deep into the ground, carried the floor on which the telescope stood. These four pillars were surrounded by a square plank house, and the whole roof consisted of a copper dome, which could be turned in the same manner as the roof of a windmill. From the peak of the dome to the bottom there was a slit, as wide as the diameter of the telescope, which could be opened and closed with pulleys and cranks. Thus, by rotating the roof and the telescope on its pedestal, one could observe the sky wherever one wanted.

Hennert was also impressed by what was offered. He was particularly struck by the way the instrument was set up. Due to the solid stone foundation, which was completely separated from the rest of the building, the instrument was protected against shocks as much as possible. Bugge also mentions this arrangement in his journal, although he seems to be most fascinated by the handy lounger that was attached to the rotating dome. This allowed an observer to turn himself around with one hand, while operating the telescope with the other hand. According to Bugge, the whole thing moved as light as a feather!

The fact that Van de Wall was so rarely in the spotlight with his telescope is undoubtedly also related to the fact that so little was done with it. The only known observation made by Van de Wall was recorded thanks to Bugge. This involved an observation of the planet Saturn, where Van de Wall claimed he had seen Saturn's rings narrowing near the edges and thickening near the planet itself. He had also seen several rings on the surface of Saturn, parallel to each other and to the large ring.

This limited use for observations is in turn related to the nature and function of scientific practice in the environment of wealthy amateurs in which Van de Wall lived. The tone here was in many respects set by the English Newtonian John Theophilus Desaguliers during his tour of a number of Dutch cities in the years 1729-1731. Desaguliers' propaganda tour contributed much to the popularization of natural science in the Netherlands.

Showman Desaguliers surprised his audience with spectacular demonstrations, where entertainment sometimes seemed to be more important than the scientific component of the argument. Commerce seemed at least as important as the transfer of knowledge. Desaguliers' Dutch tour was tightly organized and was surrounded by extensive publicity. Mediation in the sale of scientific instruments seems to have been a not unimportant secondary goal in this campaign. During his lessons, Desaguliers presented the latest of the latest and with that came the

'reflective telescopes', which he recommended in his lectures as an instrument with great qualities. It may have been partly due to this influence that the first reflecting telescopes in the Netherlands could be traced shortly afterwards. Desagulier's actions led on many places to follow-up. Various study groups emerged, led by Scientific practioners of varying depth. Various testimonies of this revival of interest have been handed down. So writes the Amsterdam Jan Wagenaar in 1737: The above quote points out three things that are important in this dilettante interest. On the one hand, there was the aforementioned aspect of sociability: the 'trading' of physics was experienced together with others. This activity was in line with the consumption of drinks and food: all of these things belonging to excellence of the domain of 'conviviality'. But there was more. As in contemporary sports, this learned enthusiasm also involved 'competition' and 'entertainment'. Scientific instruments were necessary tools for this competition. Because of all this, a scientific instrument had become more than a tool for research. An instrument was also one means of persuasion in scientific discussions. However, it could also bring people together in amazement, competition and entertainment. Such a 'machine' generated the opportunity for theological contemplation and could bring prestige to its owner. Or to put it in Walters' words: scientific instruments were convergence points for conversation, companionship, and consumption. For many eighteenth-century collectors the attraction to a scientific instrument lies not in their practical utility, but in their value as tools applied to the construction of a social image. The scientific instrument was not something to step out with into the world of 'real' scientific research. It has primarily become a status-enhancing part of material bourgeois culture.

Despite the instrument's limited scientific record, Van de Wall's bequest was received with pleasure in Leiden in 1782. After all, it was still the largest reflecting telescope available in the Netherlands. Moreover, the 8-foot reflecting telescope of Leiden University had been out of operation since 1769. The bequest of this 'excellent piece' was therefore particularly useful. The fact that Van de Wall's telescope was now several decades old was apparently not seen as an objection, which in the light of the reports that have since circulated about the exceptional performance of Herschel's new reflecting telescopes can at least be called curious. The prominent position that the University of Leiden had occupied in the firmament of Europe's learned world at the beginning of the eighteenth century had undeniably faded. Were the Leiden professor 's-Gravesande imported the first reflecting telescope into the Netherlands in 1734, it would have provided an instrument that held the state of the art half a century later, little remained of that leading position.

Dionysus van de Wijnpersse, the then professor of astronomy, was not like 's-Gravesande. In many ways he could not match his predecessor. After an on-site inspection, Van de Wijnpersse showed himself to be extremely satisfied with the Amsterdam acquisition. Leiden city supervisor Dirk 't Hart was therefore instructed to draw down the Van der Wall's observatory so that it could easily be rebuilt in Leiden. Adam Steitz, Van de Wall's last instrument maker, delivered the instrument and observatory to Leiden University with due care. The telescope would be temporarily placed there in one of the upper rooms of the Academy building on the Rapenburg, right next to the university observatory. For a final setup, Van de Wijnpersse would look for a place where the observatory could be rebuilt to be set up 'for the greatest use for astronomy and university'. In the meantime, the housing was stored in parts in the attic above the Leiden stonemasonry, 'at the city shop'.

Van de Wall's telescope in Amsterdam had not served astronomy at all, but the instrument did not have a glorious fate at the Leiden observatory either. The wooden housing has languished without a trace in the attic of the city carpenter, and the telescope has never been properly set up in Leiden either. It is highly questionable whether any observations have ever been made with it. The astronomer Frederik Kaiser, who found Van de Walls telescope idle at the observatory in 1826, later reported that the instrument welches sehr gut gearbeitet war was set up in a long room on the ground floor. Only a small part of the western sky could be observed through a hatch. But the instrument was no longer allowed to fulfill even that modest task. In Kaiser's time the large mirror had become dull and observations were no longer possible at all. The extra mirrors mentioned in an inventory of 1798, Kaiser does not mention at all, so we may as well assume that these too had disappeared. According to Kaiser, his predecessor Dionysus van de Wijnpersse had caused astronomy in Leiden to completely disappear from the world stage, through which 'the former tools' such as the 'excellent telescope by the Lord Van de Wall at the Hoogeschool entertained' had produced the least fruit in the hands of Van of Wijnpersse. With that a scientific instrument that had once represented the best that could be achieved in technical skills in the Netherlands, was reduced to a 'useless' ornament with only historical value. And even that history turned out to be misinterpreted. In 1868 at least, Kaiser was firmly convinced that the 'Van de Wall telescope' was the brainchild of the Delft mathematician Dr. Johannes van der Wall (1734-1787). An understandable mistake, since this Van der Wall had a background in which the telescope would have fitted perfectly. Not alone had this Van der Wall obtained his PhD in Leiden in 1756 with an astronomical thesis (titled Specimen astronomico-geographicum inaugurale de navigandi arte) but after that he was associated for decades as a lecturer - including teaching 'astronomy' - to the Delft branch of the Fundatie van Renswoude. But alas! From archival research it has not emerged that there was anything between the Amsterdam brothers Van der Wall and the Delft mathematician Van der Wall, not even the slightest family relationship existed. It is highly questionable whether the gentlemen would have known each other at all. Had that been different, the Netherlands might have been able to boast a 'Herschel' much earlier than England.

After all, the 20-foot focal length mirrors that Ferrner had seen in 1759 were probably the largest in the world at the time. And although they were ready for years, the merchant Van de Wall never actually had them mounted in a telescope. In 1777 Van de Wall stated to Bugge that he had given up on this project. These large mirrors have never served science either. But Oh well, that was never really what merchant Van de Wall was interested in.

The fortunes of Van de Wall's telescope

"Companies are being set up everywhere to discuss physics and conduct experiments. Several special persons make it their business to collect many and valuable instruments and treat their friends less with tasty food and drink than with a series of physical observations. There is a kind of naivety among the community there. Each seeks to become a naturalist. The merchant withdraws his hand from the writing table to hit it at the air pump and even on assembling instruments, and does not hesitate to work to the point of sweating on it. The craftsman takes time off from his work for something else, because he takes more pleasure in it."

Van de Walls telescope at the Leiden Observatory